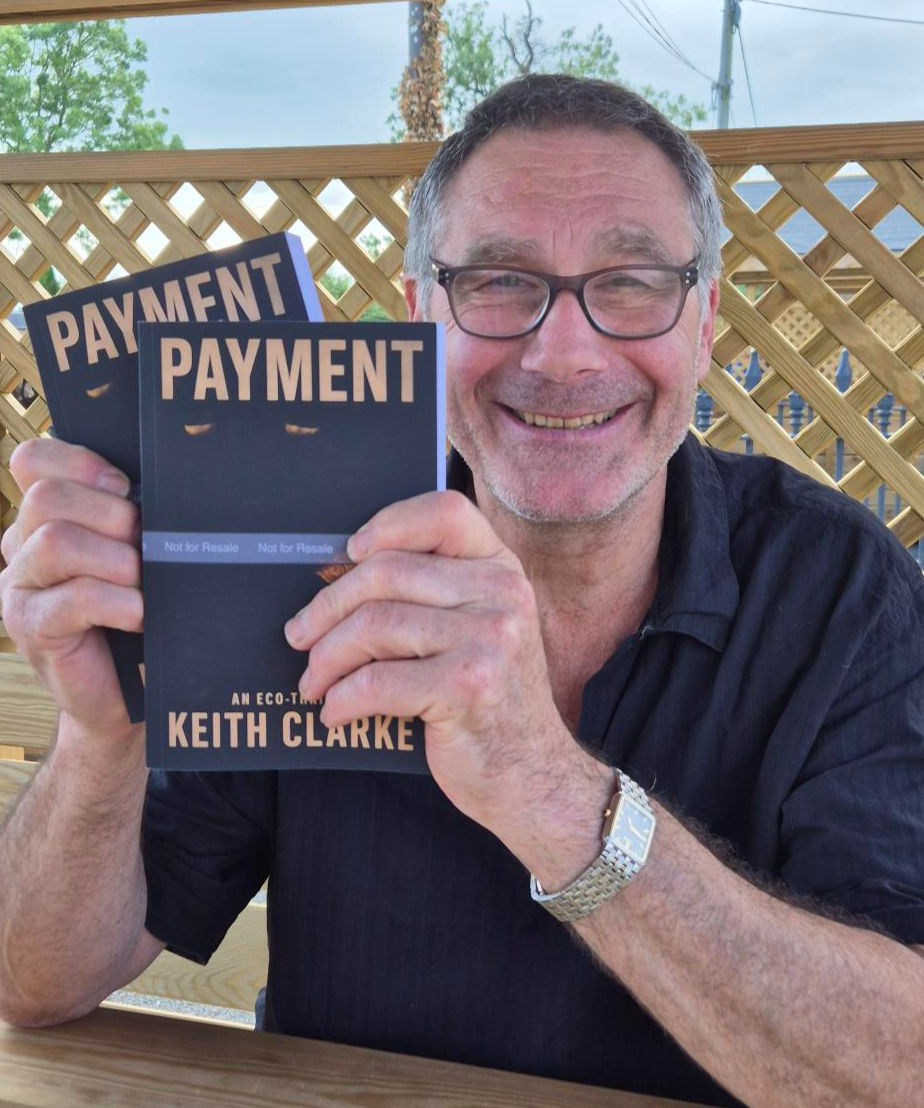

We're AI Human

- Keith Clarke

- Aug 22, 2025

- 5 min read

The following story took me one idea and one minute to create. I had the idea and Chat GPT did the rest. It's definitely my idea. It's definitely not my story. All I said was, 'write me a short story, about an author using AI who gets caught out in a very public way and is embarrassed into admitting his use of AI. Let's say a thousand words.'

10 seconds later we got this:

The Ghost in the Book

Martin Greaves had always been a competent writer, but never a dazzling one. His novels sold a few thousand copies, mostly to friends of friends or second-hand shops. His sentences were tidy, his plots predictable. Nothing to be ashamed of, but nothing to set the world alight.

And then came the sudden leap.

His sixth novel, Ashes of the Sun, was longlisted for the Booker. Critics who had dismissed him as “staid” and “reliably mediocre” suddenly wrote glowing reviews. “A master of cadence,” one gushed. “A new Dickens,” another declared, not quite sober.

Martin basked in it. He nodded sagely in interviews, shrugging when asked about his “radical stylistic evolution.” A man cannot reveal all his tricks, after all.

But he knew, as he lay awake at night, that the trick had a name. Daisy.

Daisy was the AI he had discovered one slow Sunday afternoon when, out of curiosity, he had typed a clumsy draft paragraph into a chat box and asked for a polish. The return was dazzling. Not his voice, exactly, but a sharper, cleverer version. Within a week Daisy was smoothing his metaphors; within a month Daisy was outlining chapters.

By the time Ashes of the Sun was complete, Martin had convinced himself that he was still the author. Daisy was merely a tool. A clever pen, an electric typewriter. Nothing more.

Until the Cheltenham Festival.

The organisers had been delighted to secure Martin. His meteoric rise was irresistible; ticket sales doubled. On the Friday evening he stood backstage, watching rows of expectant readers file in, the smell of damp coats and coffee thick in the air. His stomach fluttered. He knew the questions would come. He had rehearsed answers.

The chair of the session, a sprightly academic named Dr. Hannah Lorrimer, smiled warmly as she welcomed him to the stage. Applause swelled. Martin took his seat, smoothed his notes, and tried to look like a man who deserved the attention.

The first half hour was painless. Hannah asked about his childhood, his influences, his favourite writers. Martin spoke of Hardy and Orwell, dropped in a funny anecdote about his first rejection letter. The audience laughed. He began to relax.

Then came the reading.

“Would you give us a taste of the prose that has so enchanted us all?” Hannah asked.

Martin nodded. He opened Ashes of the Sun to page 212 — the passage Daisy had insisted was the book’s beating heart — and began to read.

His voice stumbled. The sentences were elegant, intricate, looping in rhythms he had never mastered. He read too fast, then too slow, like a violinist who’d only yesterday learned where to place his fingers. He finished to polite applause, but he saw it in their eyes: doubt.

“Exquisite,” Hannah said. “Now tell us, how do you do it? That cadence, that rhythm — it’s unlike anything in your earlier work.”

Martin smiled, stalling. “One evolves,” he said.

“But can you show us?” Hannah asked. She produced a slip of paper. “A little exercise, if you will. Here’s a sentence. Make it yours. Show us how you weave the magic.”

The audience leaned forward. Phones were lifted, recording. Martin’s throat dried.

The sentence on the paper was brutal in its plainness: The wind was strong, and the trees moved.

He stared at it. His mind groped for poetry. He thought of Hardy, of Orwell. Nothing. He cleared his throat. “Ah, well…”

The silence stretched. A cough echoed from the back. He muttered, “The gale bent the branches low,” then stopped, as if the rest had wandered off into the car park.

Hannah tilted her head. “That’s… nice. But not quite Greavesian.”

A chuckle rippled through the crowd. Someone whispered, loudly enough, “AI writes better than that.”

His heart thudded. Sweat beaded at his temple. He laughed — brittle, hollow. “Well, we all have our off days, don’t we?”

The hashtag was born before the session ended: #OffDayGreaves. Twitter filled with side-by-side comparisons of his awkward attempt and the shimmering prose of Ashes of the Sun. One wag posted: Maybe his AI was on holiday today.

By morning, the storm had broken. Journalists dug into his drafts, noting the sudden stylistic lurch between books five and six. Former students at his creative writing workshops tweeted that he’d once admitted “hating metaphors.” The whispers became a roar: He cheated. He used AI.

On Sunday, his publisher called. “Martin, you need to address this. Now. Denial will kill you.”

So he wrote a statement. Or rather, Daisy wrote it for him.

Then he stopped, staring at the glowing words on the screen. The irony was too much. He deleted them and began again, this time with nothing but his own clumsy fingers.

It was short, and plain:

Yes, I used AI. I thought of it as a typewriter, nothing more. But I see now that the prose people loved wasn’t mine, and to claim it was is a lie. I’m sorry.

The confession went viral. Critics who had once praised him now savaged him. Bookstores quietly removed his novels from display. His prize nominations evaporated.

Yet in a corner of the internet, a different reaction emerged. Thousands of aspiring writers admitted they too had used AI, quietly, guiltily, to polish their sentences. Forums buzzed with debate: was Martin a fraud, or just ahead of the curve?

Months later, Martin found himself in a smaller hall, speaking not to hundreds but to dozens. He had self-published a novella, clumsy but honest, every word his own. The reviews were brutal — “plodding,” “pedestrian” — but he stood straighter now.

“I can’t promise brilliance,” he told the audience, “but I can promise it’s mine. Every word, every stumble. Mine.”

And from the back of the hall, someone clapped. Slowly at first, then louder, until the whole room joined in.

Martin smiled, properly this time. For the first time in years, he felt like a writer again.

It's readable. It hooked me and I w

anted to know what happened to Martin. Do we embrace this? Or do we demonise this? I really don't think we have a choice. People are already monetising AI created books on Amazon. You tell me if you could tell if that was AI or me? I think I am a better writer than Daisy, as I call ChatGPT, but she is certainly faster! And I just read her story. And I wanted to know what happened. Isn't that the essence of a story?

PS She did the picture too. Notice the mistake? Well, we're all human.

Keith

Hillsigns Publishing 2025

Comments